Growing up, I was not a good girl. Good girls follow the rules, listen to their mothers, don’t make a fuss. They are quiet, polite, proper, and well-behaved. I rarely managed to pull that off. Branded a bad girl, I was sent to my room, grounded, and even—once or twice—threatened with expulsion from my stolid, conservative high school. Which was fine with me. Because . . .

Bad girls ask questions.

Modesty Blaise

Modesty Blaise

by Peter O’Donnell

(Series, 1965-1996)

In 1985, I was confined to bed for two weeks after some reasonably minor surgery. The TV set was a large, bulky box, and was in the living room. I am not a good patient. I get fidgety and am easily bored. So my friend Rebecca Kurland—one of the Sunday Night Poker players—came over to visit on the first Monday of my confinement. She brought me a book.

“There are eleven of these,” she said, laying it on my comforter. “I will bring you one a day, but no more. Not even if you beg.”

Not gonna be a problem, I thought, looking at the cheesy, sex-pot cover. It didn’t even remotely interest me. Sigh. I had only known Rebecca a few months.

“One per day,” she said again. “No matter what.”

I smiled gamely and nodded. We chatted for a few minutes, then she went home.

That afternoon, I discovered Modesty Blaise. I devoured the book. Totally smitten. I was on the phone to Rebecca by 7:30. “Please!” I said. “Just one more, now?”

“Tomorrow,” she said. “Around lunch time.” And then, because I suspect she just couldn’t resist, she said, “I told you so.”

By the time I had recuperated enough to be ambulatory again, I had read all eleven of the glorious adventures of Modesty Blaise and her sidekick/right-hand-man/best friend Willie Garvin. In the intervening 30-plus years, I have read them all again, many times over.

Modesty has many, many talents, and a criminal past. She’s an orphan who worked her way up to a life of understated elegance—with the occasional foray into espionage and violence. She has charm, wit, strength, endurance, skill—everything required of a kick-ass, feminist heroine. She puts Bond (and Bourne, and Batman) to shame. And she was created by a man, in the early 1960s. Go figure.

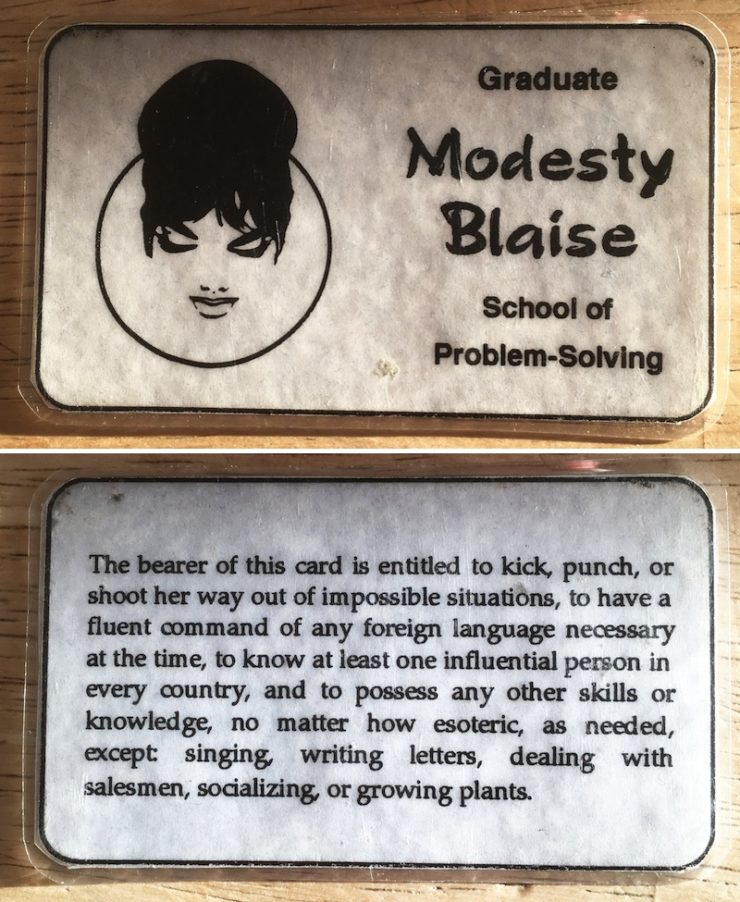

In my wallet, I carry a small, laminated card: Graduate of the Modesty Blaise School of Problem Solving. On the back, it says:

The bearer of this card is entitled to kick, punch, or shoot her way out of impossible situations, to have a fluent command of any foreign language necessary at the time, to know at least one influential person in every country, and to possess any other skills or knowledge, no matter how esoteric, as needed, except: singing, writing letters, dealing with salesmen, socializing with fools, or growing plants.

Bad girls talk openly about subjects “nice people” shy away from.

Bad girls don’t care (much) what other people think about them.

Harriet the Spy

Harriet the Spy

Written and illustrated by Louise Fitzhugh

1964

This is the most subversive book I have ever read. Possibly the most life-changing, and the most dangerous. It was published when I was in fourth grade, so I was a year and a bit younger than Harriet when I first read it. Like me, she was precocious and clever and wanted to be a writer. She had a treasured notebook. She documented life around her.

Within months, I had started keeping a dossier on my teacher, Miss Keller. (I pronounced the R in dossier; I was nine.) When she dropped a nuggets of personal fact into a conversation—the small town where she grew up, her brother’s name—I took notes. By sixth grade, my spy skills had widened to a sort of primitive spreadsheet documenting that teacher’s six outfits, which she alternated from day to day. (She found out. Things became tense).

Harriet did and was everything I wanted to be—except, of course, I didn’t want to get caught at any of it. She was intelligent, independent, feisty, not always nice or well-behaved. That was a revelation for me, at the time. She felt like a real kid, not a typical “library book” girl, who would have given up sleuthing when she discovered, by the last chapter, that sewing was much more fun!

Harriet the Spy was also my first introduction to social cruelty and betrayal. Telling the truth is not always the best idea. I had trouble parsing the moral ambiguity of that. It got easier with subsequent readings, and as I aged, but it remains one of the most cherished—yet disturbing—books in my library.

Bad girls are self-sufficient and independent.

Bad girls are not afraid to stand up for what they believe.

Point of Honour

Point of Honour

Madeleine E. Robins

2002

Madeleine and I roomed together at Interaction, the Glasgow WorldCon in 2005. Afterwards we rented a car (my credit card, her other-side-of-the-road driving skills), and motored down to London. It was a two-day journey that took us through Yorkshire, and the Moors, and to Whitby, places that, as far as I was concerned, were fictional, and were from books that I had not read, even in high school, when I was supposed to.

I have zero knowledge of classic English literature, and Mad has lots, and adores it. I asked questions, she told fascinating stories, and it was one of the great road trips of all time. We finally managed to give back the car at Enterprise’s tiny, hidden office in a mews near Hyde Park—we had no GPS and the petrol was down to fumes—breathed a great sigh of relief, and became gloriously pedestrian for another three days. Mad was researching her next book, set in London 200 years earlier, and we explored nooks and crannies and history—and pubs—as she pointed out the early-19th-century bits that lurked below and betwixt and between the rest of the 21st-century world.

Then she flew back home to kids and family, and I stayed on by myself for another few days. I’d know Mad for a couple of years, and had read a few of her short stories, but not her novels. So she left me with a paperback edition of Point of Honour, the first in the series of adventures of one Miss Sarah Tolerance.

I did not think it would be my cup of tea, really. I’m very much a 20th-century reader, have never read Jane Austen or any of the other Regency writers. But there I was, in London, with a book about the very long-ago London that the author had just been giving me a lovely guided tour of. Serendipity. Simply magic.

The premise of the book is, it seems to me, to deny its opening statement:

It is a truth, universally acknowledged, that a fallen woman of good family must, sooner or later, descend to whoredom.

Miss Tolerance is a woman of a good family who fell in love and lost her virginity outside the sanctity of marriage and is therefore disgraced. But rather than become a whore, she becomes an agent of inquiry, an 1810 private eye. She is quick-witted, quite adept with a sword (or, if the occasion demands, a pistol), and dresses as a man when the laws of propriety and society hinder any forays she might make in the guise of her own gender. She rights wrongs, solves dilemmas, and when all has been settled, retires to her cottage for a meal and a refreshing cup of tea.

I’m still not wholly converted to the glories of Regency literature, but I do look forward to the continuing adventures of Miss Tolerance with great anticipation. (There are currently three books in the series, with a fourth still a WIP.)

Bad girls challenge the ordinary, the unexpected.

The Paying Guests

The Paying Guests

Sarah Waters

2014

A confession: I have not actually read this book. I listened to it as an audio book—all 21 hours and 28 minutes of it—the autumn after I hurt my back and had to spend many, many hours lying supine in a cool, darkened room.

(I have since read the print versions of several other Sarah Waters’s books, and am in awe of her talent and skill and mastery of prose. And story-telling.)

But I’m really glad that I listened to this one, because my American eye would not have caught the nuances of class difference in written dialogue nearly as well as the British narrator delivered those subtleties of speech and accent to my ears.

After WWI, Frances Wray and her mother find themselves with a large house, but reduced circumstances. They have let the servants go, one by one, and are finally forced to take in boarders—Len and Lillian Barber, a married couple. For the first part of the book, everyone is rather formal, then Lillian and Frances begin to teeter on the edge of a forbidden attraction. Eventually, they fall, dramatically, disastrously, irrevocably.

These two strong women defy their (very different) upbringings, cultural assumptions, gender roles, societal norms, and even laws in order to be together. The book turns from a novel-of-manners to a page-turning thriller in the space of a few chapters. I stayed up way past my bedtime to keep listening, the aural equivalent of “I couldn’t put it down.”

Bad girls dress themselves and live their lives in ways that mother would not approve of.

Bad girls have a sense of humor about themselves and the world.

Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries

Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries

Kerry Greenwood

Series, 2005-present

(3 seasons on Netflix, 2012-15)

Ah, The Honorable Phryne Fisher. Terribly fashionable. Unmistakably glamourous. Handy with a pistol.

Another confession: I have only read one of the twenty books. But I have repeatedly binge-watched the 34 episodes of the TV series based on them over the last two years. Over and over and over.

I was at a house party with Rachel and Mike Swirsky, Na’amen Tilahun, and a few other people I’d just met that day. We were discussing guilty-pleasure TV, and Na’amen told me that I must watch Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries. So when I got home, I did. Three episodes in one day, happy as a clam—until I discovered that Season Two would not be released in the US for another two months. I had to force myself to ration the remaining ten episodes—one every three or four days—so I wouldn’t go into premature withdrawal.

It is a visually stunning show. Still, if you know me, you know that I am so not into fashion, or clothes, or shoes, and the 1920s is a bit early for my historical-recreation tastes. Nor do I have a fascination with Melbourne (Australia) and its checkered past.

But.

I adore Phryne Fisher. For her snark, mostly. Born in poverty, she enlisted as a nurse in the Great War, and when it turned out that none of her very upper-class male relatives had survived the conflict, she inherited a title and a boatload of money. Her best friend is a dapper, Sapphic doctor at a woman’s hospital. Phryne is rich, beautiful, smart, irreverent , does not suffer fools, and takes no prisoners. She does take lovers, as often as she chooses, owns a gold-plated revolver, speaks a smattering of several languages, and can hold her own in a fight, even if it means getting blood on her cloche.

After the war, she re-invented herself as a Lady Detective, consulting with the local police, whether or not they want her to. She wears trousers as often as she wears the latest gowns, carries a dagger in her diamante garter, can pick locks and mix martinis. She is sensible, impetuous, intuitive, competent, generous, and kind.

Phryne, Lillian and Frances, Miss Tolerance, Harriet, and Modesty.

Bad girls dance where they want to.

Ellen Klages is the acclaimed author of the Scott O’Dell Award-winner The Green Glass Sea, and White Sands, Red Menace, which won the California and New Mexico Book awards. Her short fiction, previously collected in the World Fantasy Award-nominated Portable Childhoods, has appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, and has been translated into more than seven languages and republished worldwide. A graduate from the Second City’s infamous Improv Program, Klages also holds a degree in philosophy, which led to many randomly-alliterative jobs such as proofreader, photographer, painter, and pinball arcade manager. Her newest collection, Wicked Wonders — full of tales about bad girls and their friends — is now available from Tachyon Publications, and contains several cross-over stories for fans of Passing Strange, her Tor.com novella. Ellen lives in San Francisco, in a small house full of strange and wondrous things.

Ellen Klages is the acclaimed author of the Scott O’Dell Award-winner The Green Glass Sea, and White Sands, Red Menace, which won the California and New Mexico Book awards. Her short fiction, previously collected in the World Fantasy Award-nominated Portable Childhoods, has appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, and has been translated into more than seven languages and republished worldwide. A graduate from the Second City’s infamous Improv Program, Klages also holds a degree in philosophy, which led to many randomly-alliterative jobs such as proofreader, photographer, painter, and pinball arcade manager. Her newest collection, Wicked Wonders — full of tales about bad girls and their friends — is now available from Tachyon Publications, and contains several cross-over stories for fans of Passing Strange, her Tor.com novella. Ellen lives in San Francisco, in a small house full of strange and wondrous things.